Stolen childhood: Investigation into Karamoja’s child trafficking crisis

On the busy streets of Kampala, you may see children moving between cars or sitting along the pavements.........many look tired, with eyes heavy and faces drawn. Some sit along the pavement, knees tucked under chests, while others tap gently on car windows as traffic slows.

An illustration of the writer (centre) travelling to Napak.

THE GENESIS

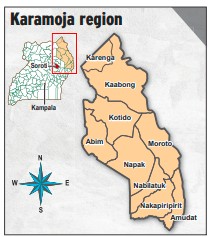

KAMPALA - Karamoja, located in the remote northeastern part of Uganda, is a region of striking contrasts and deep cultural heritage. Despite its long history of marginalisation and periods of conflict, Karamoja today is a place of resilience and transformation.

The once conservative Karimojong community continues to balance age-old pastoral livelihoods with emerging forms of economic activity. First-time travellers are drawn to its untouched wilderness, diverse wildlife and cultural authenticity.

However, it is unfortunately one of the areas where child trafficking remains a serious and ongoing problem. Poverty, food insecurity, limited access to education, and the disruption of traditional livelihoods are some of the many reasons that have made children from Karamoja vulnerable to exploiters, who coerce them into forced begging and domestic servitude.

Nevertheless, there is growing awareness and active efforts from local communities, authorities and non-governmental organisations to combat child trafficking in Karamoja.

In this five-part series, our undercover journalist spent 75 days in Karamoja and brings you the nerve-racking details of the cartel profiteering from children used as street beggars.

An incoherent murmur rises, half-plea, half-prayer... “Mpaayo ekikumi” (give me sh100), they say while signalling they desperately need something to eat To the first timer, it is a pitiable sight.

On the busy streets of Kampala, you may see children moving between cars or sitting along the pavements, their small frames made thinner by long days without steady meals.

Many look tired, with eyes heavy and faces drawn. Some sit along the pavement, knees tucked under chests, while others tap gently on car windows as traffic slows.

Others roam in loose clusters, whispering to each other in Karimojong language. When a passer-by pauses, even briefly, the children’s eyes brighten. A hand extends, small and uncertain.

An incoherent murmur rises, half-plea, half-prayer... “Mpaayo ekikumi” (give me sh100), they say while signalling they desperately need something to eat To the first timer, it is a pitiable sight.

To the commuters, mainly taxi drivers, who treat them with disdain, there is more to these street kids than meets the eye. They are a ‘business’, as one commented. The conveyor belt that churns them is at its peak in the months towards Christmas.

The question is: Who is behind the trafficking of the Karimojong children? The trafficking of Karimojong children, especially to the streets of Kampala, where they are used as beggars, can be traced to the early 2000s.

Vulnerable children from Karamoja begging for money from car drivers at a traffic light junction in Kampala, along Entebbe Road. It is alleged that the children are trafficked from Karamoja and used to beg as a business.

Then, children would travel from Karamoja, make stopovers in Busia and Jinja, before proceeding to Kampala. Then, many people used to pity the haggard-looking and would empty their wallets in empathy.

No one thought this was a well-orchestrated plan, with seasoned masterminds minting money using these innocent souls as beggars.

In 2008, the Government, through Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), came up with a plan to forcefully remove the Karimojong children from the streets of Kampala.

They were at first taken to Kampiringisa juvenile detention facility in Mpigi district for rehabilitation. But the children kept reappearing in multitudes. Some returned as rogues, menacingly demanding money.

Deny them money, and a thick phlegm of mucus or saliva will end up on your well-pressed suit before they casually stroll off. Authorities later revised the operation, and children would be taken back to Karamoja to reconnect with their families, because Kampiringisa is a place for juvenile offenders.

How the investigation started

A New Vision undercover journalist travelled to Karamoja and followed the child trafficking racket for two months and two weeks. The journalist was also able to trace the co-ordinators, who are based both in Katwe, Kampala, and Napak districts.

For years, I have been following up on the exercise of removing Karimojong children from the streets of Kampala by KCCA.

The exercise at first sounded promising, and everyone hoped it would yield permanent results. Despite efforts by KCCA, there have not been permanent measures to remove the children from the streets.

These children are being used by a group of people, who position them on different streets of Kampala to beg. Their number keeps increasing every other day.

According to a report released on the World Day against Child Labour in June, the International Labour Organisation and UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) noted that around 87 million children in sub?Saharan Africa were engaged in child labour last year.

These were denied their right to play, learn and simply be children. While interacting with a source, he intimated to me that four schools in Karamoja are rehabilitating children picked from the streets of Kampala and enabling them to attend accelerated school programmes.

The source stressed that the idea to take children back to school came up as a solution to curb child trafficking from Karamoja to Kampala.

The idea sounded good. So, I decided to visit the schools where the children are taken in Karamoja, engage with the communities, talk to the children and fi nd out what pushes them to Kampala.

Journey to Karamoja

After speaking at length with my source, I decided to travel to Napak, one of the districts in the Karamoja sub-region, with schools where former street children are studying.

Napak is leading in child trafficking in Karamoja, with 90% of the children on the streets of Kampala coming from the district. The 10% come from other districts in Karamoja, according to authorities.

However, I was advised to seek permission from the Ministry of Internal Affairs before travelling to Karamoja.

I duly sought permission from a government official, who allowed me to access schools, since they are guarded by the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF). The soldiers help school authorities to protect and monitor children, to keep them from running away or being trafficked.

Children begging by a pavement on Jinja Road.

What dives them to the streets?

What perks would sway one to travel over 500km from Karamoja sub-region to stay on the streets of Kampala? Many people I interacted with speak of misery and abject poverty as the major factor driving the children to Kampala.

But there are many other parts of Uganda affected by poverty, such as the Busoga sub-region, some worse than Karamoja.

“So, why are children from areas like Busoga not on the streets of Kampala begging?” I ask myself. When I travel to Napak, I realise that there are several Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) claiming to be giving a hand to vulnerable people, especially children.

Besides, the Government, through the office of the Prime Minister, also has programmes in Karamoja, and there is a whole ministry for the sub-region’s affairs that has been running for decades. But still, efforts to get children off Kampala streets have failed.

One of my sources in Napak, a police officer with knowledge of child trafficking, warned me, “The Karimojong are hostile; you need someone to guide you around.”

The area has no reliable electricity, food, or water. The roads are not good, and insecurity is high. I was not moved by this information because I have been involved in riskier assignments than this.

But I was a little anxious about what to expect, especially the language barrier. I had two options: travelling by Kakise bus to Soroti and then connecting to Napak, or using a Gateway Bus that goes to Moroto via Soroti and Napak.

This sounded easy, though it was my fist time traveling to Karamoja. By 6:30am on May 13, I was already in the Namayiba bus terminal in Kampala, ready to take off. I left Kampala with a morning Kakise bus at 7:00am, which dropped me in Soroti town.

I was charged sh30,000 from Kampala to Soroti. While on the bus, I was observing other passengers. A lot was on my mind.

Napak is leading in child trafficking in Karamoja, with 90% of the children on the streets of Kampala coming from the district. The 10% come from other districts in Karamoja, according to authorities.

Will I find the children? What would be my escape route if things went wrong? Will I get a story? How about the language? How will I interact with the Karimojong? How will I be moving in the villages? All these questions were lingering in my mind.

I took a deep breath and told myself, “I will do it”. In the bus, I sat next to a young boy aged about 10, who was going on holiday in Soroti. We went chatting, eating and listening to music.

He was my route director. I enjoyed the nine hours from Kampala to Soroti. Upon arriving in Soroti, a female passenger asked me whether Soroti was my destination. I told her I was still proceeding to Napak. She contorted her face and gazed at me as if to say, “You are in deep trouble.” I muttered to myself. “I am ready.”

She described Napak as a deadly, insecure district. She asked whether I was a journalist, a security officer, or working with an NGO. I told her I was just a ‘researcher’. “You have many more hours to get there. You are likely to arrive at 11:00pm,” she said.

As I was still looking around for the taxi to take me to Napak, another male passenger offered to direct me. He was my knight in shining armour. He also helped to carry my hand luggage to the park. It was getting late.

He advised me to do some shopping at the supermarket since I was likely to arrive late in Matany, which I did. But I failed to get a taxi. The only available transport means were open trucks and private Saloon cars.

I opted to board a Saloon car — a Toyota Noah. It took three hours to fill up, and we were packed like sardines. We set off for Napak at 7:00pm. In the Saloon car, I was told to sit on the car console with legs spread apart; one on the driver’s side and another on the co-driver’s side.

Thankfully, it was an automatic transmission. I shudder to think of what would happen if it were manual, with the driver repeatedly engaging gears between my legs.

For the entire close to four hours of the journey, I sat in this uncomfortable position.

Along the way, passengers would be picked up, while others would disembark in dark, open places by the roadside.

Conversations in the car were hushed, short and cautious. I was scared; my heart was an out-of-control pendulum.

Fearing we could easily be ambushed by cattle rustlers, I at some point asked the driver why he kept stopping to pick up passengers from the wilderness, and at night.

And every time we would approach a trading centre, I would ask him whether we had reached Matany.

We passed through several checkpoints, but our car was only checked once at a place called Iriiri. I was worried that I could be left in an isolated place. The reassuring tone of my host in Matany during a phone conversation kept me going.

Read part two here: Demystifying the myths: The Karamoja we never hear about

Read Part three here: How children are moved from Karamoja to Kampala streets

Read part four here: Leaders demand crackdown on Karamoja child trafficking rings

Part five will be available in tomorrow's New Vision of Tuesday, December 30